09/18/2025

Prologue: I wrote the original version of this essay in 2018. It was the basis of my inaugural lecture as Emil and Elfriede Jochum Professor and Chair at Valparaiso University in Indiana. The original essay predates the tragic assassination of Charlie Kirk and a number of acts of political violence. I have updated the first part of the essay, but the core argument remains the same: we have to learn how to see and honor the image of God in our opponent. The original essay was published in Valparaiso University’s Cresset, which is no longer published.

During the seven years that I studied and worked in Washington, DC, I became familiar with a notorious phrase: “The Beltway.” If you have ever attempted to drive in and around DC, you have probably been on the Beltway at some point, highway 495 that forms a belt around DC and cuts through Maryland and Virginia. To be sure, driving on the Beltway puts one at risk of a long delay, missing an exit, or having an accident: it is terribly busy, and my late wife described it as akin to the “Indy 500.” A related term is even more notorious: “inside the Beltway,” a reference to the national political gridlock that unfolds every day in our nation’s capital. If my reference to business conducted inside the Beltway evokes feelings of anger or suspicion about the federal government, or if you are convinced that the devil is the father of the details conceived there, then you have a sense of the spirit of anger prevailing in our times. People are angry at elected officials for making deals that are not in their best interest. People feel alienated by policies and their underpinning ideologies that appear to favor other interest groups without accounting for their wants and needs. People fear the advent of the unknown: they are afraid of immigrants who come here in search of work, and of politicians and activists who advocate for new policies that challenge their current way of life and conflict with their core values.

The anger, fear, and alienation experienced by many in our time results in a number of behavioral patterns. Among the most troubling patterns of our time is the gradual disappearance of dialogue. Increasingly, vicious polemical attacks that have the primary purpose of demonizing the position of the other have emerged as the pattern replacing dialogue. The evidence of such polemical attacks is everywhere, and the relative anonymity of social media has unleashed an entirely new arena where one can not only commence a fierce attack against one’s opponents, but can invoke riotous, scathing condemnations of others without even knowing their names or seeing their faces.

In other words, the purpose of engagement in our time is to attain a personal triumph over one’s opponent: the spoils of victory for the one who seems to have the upper hand in such engagements is the humiliation suffered by the other. When one ideologue celebrates their triumph over a defeated opponent, the fumes generated by a graceless and boorish victory symbolized by exaltation in the humiliation of the loser function as fuel that renews the cycle of anger, alienation, fear, and suspicion, and enhances its intensity. Today, this scene unfolds in digital spaces able to host international arenas of brutal public trash-talking; the explosion of digital media and relatively anonymous exchange has standardized the practice.

Historians and sociologists have devoted considerable resources towards unearthing the causes of global anger and alienation. Economic evolution is certainly one cause, especially when industrial decline, outsourcing, and automation results in the discontinuation and disappearance of jobs. But it is not only the absence of equal access to jobs and economic stability that fuels anger and alienation. The “culture of separation” that defined modernity and afflicts post-modernity permeated all aspects of life: citizenship, religion, and national identity, among other aspects (Bellah et al, 1985, 275-7). Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Israel-Hamas war, the geopolitical saber rattling throughout the world, and the epidemic of gun violence and political assassinations in America reveal the tragic outcome of the culture of separation.

Almost ten years ago, John Judis demonstrated how President Trump fits into the pattern of creating a profile as an anti-establishment populist in his first campaign vow to restore manufacturing jobs and reform immigration, a movement that had an echo among liberals with Bernie Sanders (Judis 2016). Anti-establishment anger can become infectious and generate incredible and constructive energy – Americans witnessed to this energy when the students of Parkland High gathered themselves to protest publicly against the gun establishment. Instances of constructive and destructive anti-establishment energy threaded through the womens’ marches of 2017, the protests over George Floyd’s killing, and the violent attack on federal Capitol on January 6, 2021. However, working together to discover the truth is not an attainable objective when the intensity of polarized polemical exchanges reaches a fever pitch: the objective is to publicly humiliate one’s opponent, to expose them as flawed in some way, so that one’s own position will be endorsed.

Scholars of ritual studies like to quote a saying that is attributed to Native American folklore: “never judge a man until you have walked at least a mile in his moccasins.” In the rest of this essay, I will explain how a Christian spirituality of dialogue can restore the art of engaging one’s opponent if the engagement is truly dialogical.

A Spirituality of Dialogue with the Other: Look in the Mirror

The Christian tradition is saturated with teachings and words of wisdom on the harm caused by playing the blame game. Jesus’ sermon on the mount in Matthew is filled with teachings that chart a path of discipleship rooted in pouring one’s self out for the sake of the other, even if blows are received in return. Prayer should be private, fasting performed without making a spectacle of one’s self, forgiveness is commanded, one is not to judge others, nor even point out their faults: the disciple who casts his gaze on the faults of the others will be exposed as a hypocrite, and not a disciple, and the teaching is so radical, that good must be returned for acts of evil. Discipleship compels the hearer to adopt Christ and his kenotic love as the pattern to be adopted in the process of daily Christian living. Performing these acts is a mode of taking up one’s cross, and the telos is perfection (Mt. 5:48). When Christians encounter these teachings, they recognize them and must navigate the tension between Jesus’ authoritative teaching from the mountain, that fulfills the law of Moses, and the cultural ethos that claims “nobody’s perfect.” The hearer finds little comfort when Christ instructs the hearers to “enter by the narrow gate,” because the perfection commanded by Christ seems unrealistic and, quite plainly, impossible to achieve. There is a significant gap between worshipping the crucified and risen one who personifies discipleship and committing to threading these precepts into the fabric of daily behavior. Yet it is the decision to forsake or ignore Jesus’ new commandments from the mountain that leads Christians to respond to anger with wrath, and to strike one’s opponent with even more force than the blow thrown by the opponent.

An examination of Christian tradition shows a collection of figures who received Jesus’ teaching and attempted to apply them as rules for communal living and engagement of the other. These examples from tradition occur in a variety of contexts: Cappadocian monastic contexts from late antiquity, liturgical rites passed down through several generations, and the narratives of pastors, monastics, and laity responding to dangerous ideologies and wars that claimed the lives of millions.

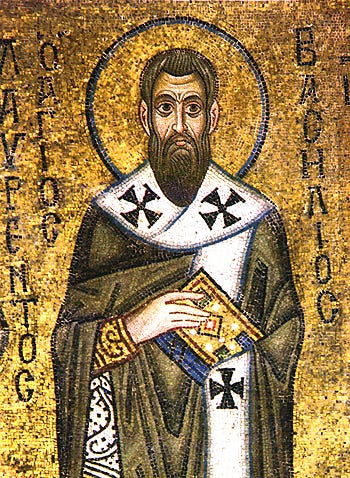

Our first source comes from a philosopher, bishop and ascetic known as Basil the Great (330-379). In the Christian world, Basil is beloved because of the prayers attributed to him, his theological progeny (having an equally gifted brother and a saintly sister), his theological treatises that became the foundation for the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, and his ascetical writings. Instructive for our purposes is Basil’s Homily (no. 319) on Humility. The context of this homily suggests that Basil was addressing people who lived and related to one another in the world of the late-antique city. Basil is critical of those who indulge in the glory and honor that comes with political success (Basil, trans. Wagner, 476):

But also because of political honors do men exalt themselves beyond what is due their nature. If the populace confer upon them a distinction, if it honor them with some office of authority, if an exceptional mark of dignity be voted in their favor by the people, thereupon, as though they had risen above human nature, they look upon themselves as well nigh seated on the very clouds and regard the men beneath them as their footstool. They lord it over those who raised them to such honor and exalt themselves over the very ones at whose hands they received their sham distinctions.

In the public sphere, Basil seems to be warning against the kind of elitism that comes with rank or stature in the political hierarchy. What’s important for our purposes is the politician’s perspective of the other: they exalt themselves over others and view them as their footstool. Basil describes the steps the exalted need to take to learn how to see themselves, and then how to see others (Basil, trans. Wagner, 483):

If you appear to have something in your favor, do not, counting this to your credit and readily forgetting your mistakes, boast of your good deeds of today and grant yourself pardon for what you have done badly yesterday and in the past. Whenever the present arouses pride in you, recall the past to mind and you will check the foolish swelling of conceit. If you see your neighbor committing sin, take care not to dwell exclusively on his sin, but think of the many things he has done and continues to do rightly. Many times, by examining the whole and not taking the part into account, you will find that he is better than you. Such reminders as these regarding self-exaltation we should keep reciting constantly to ourselves, demeaning ourselves that we may be exalted, in imitation of the Lord who descended from heaven to utter lowliness and who was, in turn, raised to the height which befitted him.

Basil proposes an ascetical practice that speaks directly to the kind of exaltation to which one enjoying a high rank might be prone. The errors of one’s past are useful in this regard to avoid the temptation to exalt one’s self and treat others like a footstool. Basil employs hyperbole when he suggests that we are to demean ourselves, but the point of adopting this habit is twofold: to learn how to see good in one’s interlocutor, especially when one considers the whole of that person; and to adopt the pattern of Christ himself. Our descent into utter lowliness is not for self-torture, to beat ourselves up: rather, it is to follow the pattern of Christ whose lowliness was in service to others. The two practices work together: we find fault in ourselves first to confront our own ugliness, and it is only when we have cleaned the lenses of the eyes of our souls that we are able to see that the other person we’re engaging is, in fact, naturally good. Cultivating the habit of humility is designed to be relational and dialogical. In a longer passage, Basil advises hearers to be modest in all ways of life, to avoid embellishment of speech, and to be “free from pomposity” (Basil, trans. Wagner, 484). Adopting a habit of modesty in the way that we talk and think of ourselves leads to new ways of dialoguing with others.

Basil offers simple instructions:

Be obliging to your friends, gentle toward your slaves, forbearing with the forward, benign to the lowly, a source of comfort to the afflicted, a friend to the distressed, a condemner of no one” (Basil, trans. Wagner, 484).

The teaching goes so far as to avoid even listening into a conversation involving gossip: adopting the habit of attending to one’s own sin sharpens the senses of seeing and dialoguing with others. One learns how to act with radical charity towards the other through practice, but in this sense, the root of the enterprise is taking on an identity of humility and refusing to exalt one’s self, reserving that praise and glorification for God alone.

Basil’s practical instructions for adopting an identity of humility re-emerge in the unique person of Paul Evdokimov, a lay theologian who was born in St. Petersburg in 1900, but immigrated to Paris in 1923 in the tumult of the Bolshevik Revolution (Plekon 2002, 109). Evdokimov received his doctorate in theology from St. Sergius Institute in Paris, and assisted in hiding and defending Jews during World War II. While he engaged administrative work by directing residences, he was active as a writer and participant in local ecumenical dialogue. Evdokimov’s writings touch on numerous subjects, but it is his sense of tradition that is most intriguing. Responding to the abrupt and fast-paced changes of his times, one of Evdokimov’s most original proposals was for the adoption of a monastic life by lay people in ordinary daily life applying the principles of the desert in each situation, focusing on service to God and one’s neighbor, with liturgy shaping a habit of service extending into the world, embedded in everyday life (Plekon 2002, 124).

In writing about the Christian quest to acquire the Holy Spirit, Evdokimov says that the process begins by coming to terms with yourself. Learning one’s self requires a deep journey within:

Our vigorous penetration into the darkness of our heart of hearts, though it is a formidable undertaking, gives us the power to judge ourselves” (Evdokimov 1998, 167).

Evdokimov acknowledges that this is a rigorous journey, so he advises that one should put on an “ascetic diving suit,” because the goal is to “seize our perverted will” (Evdokimov 1998, 167). As the ascetic comes to terms with the perverted will, he or she is ready to ascend – Evdokimov describes the point of this ascent as a conversion, and the objective is to become a human who loves – the love is not emotional, but crucified love, because an identity of true humility is in a constant process that is never complete – the one who is converted always identifies themselves as a sinner (Evdokimov 1998, 168).

How does this relate to the way we engage others, especially our opponents? Adopting an identity of humility is the “art of finding one’s own place,” and accepting that place without hoping for praise or exaltation. Evdokimov refers to the humility of John the Baptist who is content to be the “friend of the bridegroom,” and Mary, who is joyful in being the “handmaid of the Lord,” both principal figures of the New Testament and Christian tradition whose humility is patterned after Jesus’ humility. Evdokimov asserts that self-centeredness makes the universe revolve around the human ego – egomania is manifest when one refuses to bow before the other.

Evdokimov is sensitive to the possibility of confusing humility with humiliation:

No confusion is possible between humility and humiliation, weakness or spineless resignation. Humility is the greatest power, for it radically suppresses all resentment, and it alone can overcome pride” (Evdokimov 1998, 169-70).

Evdokimov’s reinvigoration of asceticism enjoys a strong coherence with Basil’s: the ancient and modern theologians call upon everyone to become an ascetic. The details of this process require brutal self-honesty: there is a fine line between admitting one’s sin to one’s self, and striving to see the good in one’s interlocutors, and punishing one’s self because one is bad. Basil proposes an ascetical practice designed to embrace humility because for Christians, exaltation is reserved for God alone, always. Accepting one’s place as not exalted, but flawed quiets the passions of resentment – which are rooted in desiring exaltation, a temporal honor that comes with victory over one’s opponent.

If Basil and Evdokimov emphasize the ascetical process of adopting an identity of humility, Maria Skobtsova teaches us to learn how to see our opponents as brothers and sisters in Christ. Mother Maria wrote to reframe the way her fellow Russian immigrants understood the experience of praying before icons, in both private and public settings. Her writing is occasionally razor sharp in her critique of ossified ritual forms of the synodal period of the Russian Church – this is particularly evident in her famous essay exposing the five types of Russian ritual spirituality as internally oriented (Skobtsova 2003, 140-86). Mother Maria’s essay on the mysticism of human communion charts a new spirituality rooted in the public ritual acts of venerating icons during the celebration of the Divine Liturgy. Knowing that Russians recognized the connection between the ritual veneration of icons and their prayer before icons in the altars of their homes, Mother Maria suggests that one should learn how to see the world as an iconostasis, so that we would revere the people with whom we interact on a daily basis with the same piety we offer to the saints on the icons in church and at our homes (Skobtsova 2003, 80-1). Mother Maria is quite blunt in her description of the requirement for the Christian: to revere with piety men who act inappropriately, drunken neighbors, and lazy students because they are icons, bearing the image of God as the saints whose icons we venerate (Skobtsova 2003, 81). Mother Maria goes on to argue that this is the purpose of the liturgy itself, as she claims (rightly) that the liturgy is offered for the life of the world. Mother Maria refers to the ritual act of offering when the deacon (or priest) lifts up the bread and the cup during the Eucharistic Prayer and the priest says, “Offering You your own of your own, on behalf of all and for all” (Skobtsova 2003, 81). The point of participating in the liturgy is not primarily for the consecration of bread and cup into the Lord’s body and blood, but for people to be transformed so that their daily lives would consist of service “on behalf of all and for all.” This service is rooted, again, in Christ’s own pouring out of himself, his taking on human nature in utter humility (Skobtsova 2003, 78-9). Like Basil of old and her contemporary Evdokimov, Mother Maria recognized the connection between adopting an identity of humility and engaging with others with radical charity. Her blunt example of seeing unpleasant people as icons is an appeal to sharpen spiritual senses, to learn how to see one’s enemy in a new way, and to act by loving them.

The habit of humility implies a willingness to dialogue. Dialogue is antithetical to the preference for division that pervades our contemporary culture. But dialogue is itself integral to Christian discipleship. The Czech Catholic theologian Jarosław Pastuszak draws from Trinitarian theology to relate the Word of God (Logos) as intrinsic to human communication: when humans truly dialogue with one another, they have access to the divine perspective (Pastuszak 2015, 174-6). Obviously, dialogue can contribute to sustaining human life: building edifices, creating treaties, developing new technologies for medical treatment all depend on dialogue (Pastuszak 2015, 174). Pastuszak laments the postmodern tendency to make the material and spiritual spheres mutually exclusive: he claims that withdrawal into cushioned orbits such as religious and secular leads people to individualism, which breeds egocentrism (Pastuszak 2015, 168). A willingness to dialogue may result in encountering the other person’s otherness or strangeness, but Pastuszak claims that participating in that dialogue permits the partner to encounter God in the other, and God in himself as well (Pastuszak 2015, 178).

The prospect of encountering strangeness in the other person seems reason enough to hesitate from joining the dialogue. It is a hesitation many of us experience if we are not prepared on how we should act, especially if dialogue is understood as a demand for capitulation to that otherness, or if one fears that fidelity to their own principles will result in conflict. In other words, dialogue is dangerous: the fear of the unknown outcome of irreconcilable differences opens the door to opting for division instead. But withdrawal from dialogue enhances fear because it prohibits us from seeing and encountering the other, so the images we conjure of the others are distorted. Another Czech theologian, Tomáš Halík, points to the outcomes of refusing to participate in dialogue with others (Halik 2015, 107). He claims that a mutual exclusivity of secular and religious causes problems when tensions rise because secular politics lacks the language to properly express emotions, so people “grasp” for religious language. The religious vocabulary has tended towards depicting an arena, or battlefield, in which the other is the enemy who must be eradicated. In the recruitment of bellicose language, the wrong enemy is identified: Halík implies our ascetical tradition when he says that war is to be waged against one’s own moral failings, not against the dialogue partner. Halík and Pastuszak are arguing that Christians should be willing to dialogue with secular humanists as well as people of other religions for the purpose of finding common ground. Their harmonic warning about the perils of Christian triumphalism used as a weapon against the other fits our thesis, as Halík says that this tactic is a secularization of the Church’s eschatological vision (Halik 2015, 109). In other words, using Christian language to sort our neighbors into good or bad makes them into angels of darkness and us into God. Nothing good comes from this paradigm, and the triumphalists end up as idolators.

The voices speaking to us here promote the urgency of dialogue and the habit of humility from dangerous, life-threatening contexts, which was especially the case for Mother Maria. Dietrich Bonhoeffer also emphasized the urgency of dialogue during a time of grave danger. Bonhoeffer’s voice resounds because of the similarities of his context with ours, as he was committed to maintaining transnational dialogue among all the Churches when univocal fidelity to a nationalist Church was trending. Keith Clements asserts that Bonhoeffer promoted an ecumenical vocation rooted in the need for the Churches to maintain their links, to work together to establish a new and just order (Clements 1999, 158). But Bonhoeffer himself offers the most important point about dialogue:

Peace is confused with safety. There is no way to peace along the way of safety. For peace must be dared. It is the great venture. It can never be safe. Peace is the opposite of security. To demand guarantees is to mistrust and this mistrust in turn brings war. To look for guarantees is to want to protect oneself.

Clements says that this excerpt has become something of a sacred text, it is quoted so often, but it is relevant because it is compatible with our thesis on the habit of humility. Learning how to humble oneself and approach the other with love will result in making oneself vulnerable to both the other and to God.

Perhaps the most striking characteristic of these teachings on adopting humility and remaining faithful to dialoguing with one’s opponents is that it is manifest not only in the teachings, but in the very lives of the people featured in this exercise. Evdokimov, for example, hid and protected Jews during the period of Nazi oppression and devoted his life to serving underprivileged and marginalized youth, many of whom were immigrants, as the director of a residence (Plekon 2002, 109-10). Bonhoeffer strengthened his commitment to ecumenical dialogue even though finding a quiet place within the nationalist and isolationist cells of the Church in Germany would have been a safer option for him (Clements 1999, 167-8). Their witness demonstrates that the Christian tradition of adopting a habit of humility and approaching one’s opponent with love is not a naked teaching unattainable for ordinary people, but one that comes to life in flesh and blood human beings.

Conclusion

This essay suggests that the Christian identity of humility has deep roots in tradition, beginning with Jesus himself and threading through each generation up until today. Humility leads the Christian to dialogue with the other, enabling the Christian to see the good in the other while refusing to condemn them. These teachings depict a beautiful humanity, one that is able to live together in peace without erasing differences. Why, then, has this tradition essentially been ignored while the tendency to slander and humiliate one’s opponent has ascended? Christians must be ready to answer this question, because the blood of the victims of radical political violence and war cries out from the ground and demands God’s justice.

Let us turn again to Scripture: reserving exaltation for God while constantly confessing one’s sinfulness amounts to foolishness in the world. As humankind pursues economic opportunity and stability, finding the competitive edge to climb the ladder consistently nourishes the tendency to proclaim one’s self as superior to one’s peers. Like the gospel of the cross, human humility is foolishness to the world because refusing to exalt one’s self seems to cede all competitive advantage to one’s opponents. Jesus spoke so simply about the preponderance of narcissism, perhaps epitomized by his exposure of the egocentrism of the Pharisees, who “love the best places at feasts, the best seats in the synagogues, greetings in the marketplaces” (Mt. 23:6-7). No institution or profession is exempt from the crisis of discourse as trash-talking - not even the Church or its clergy. Rare is the institution that that does not systematize incentives for advancement in the ranks that stimulates competition among those who want the most “exalted” position. In this scenario, the Gospel tradition of an identity of humility simply gets in the way of systems that reward not only achievements (this is a good thing), but the sycophantism and brutal competitive positioning that breed narcissism and make it impossible for one to truly see the other as they really are because all of one’s energy is devoted to self-exaltation. Turning to the Gospel image of people who adopt Christ’s utter humility as a pattern would stifle the system, just as Jesus’ appearance and merciful acts in Seville threatened the religious order perfected by the Grand Inquisitor in Dostoevsky’s “Brothers Karamazov” – the Grand Inquisitor knows that Jesus has “come to hinder us,” so he threatens to burn him as the “worst of heretics.” For much of Christian history and in our time of exalting in our opponent’s humiliation, the holy tradition of Christian humility has become a heap of ashes. So permanently adopting an identity of humility seems impossible because it has always been and remains countercultural – and it always will be.

People of good will have admired the Christian tradition of humility, and for many, there are other stumbling blocks that make them pause before committing to humility. Let us begin with submission. Doesn’t the habit of humility I have presented here amount to submission to aggressors? We need to reflect at length on the distinction between humility and humiliation. Humility does not necessitate forsaking one’s own principles to avoid conflict. To be clear, humility cannot be translated as submission to verbal and physical aggression. By no means does humility call for anyone to tolerate abuse of any kind. The radical humility of our collection of figures is rooted in the cross of Christ – it is formed by the constructive and transformative power of God’s kingdom. Refusing to respond with aggression with even more negative ferocity exposes the human decay caused by uncivil discourse. The one who abuses damages their own soul by covering the human faces of their opponents with the false masks of demons. Embracing the way of humility opens the doors for the healing and transformation of those who harm themselves by choosing abuse over charity.

The next obstacle is the oft-repeated notion that only a chosen few are capable of becoming humble and reserving exaltation for God alone, but that this is impossible for the masses. There is a difference between impossible and hard, and Christians need to remember that the way of the cross is always narrow and requires both effort and divine mercy. Different religious traditions agree that following God is a lifelong struggle, exemplified by Jacob wrestling God, by the excruciating battle against one’s self reported by Augustine and Luther, and by the tears described as drops of blood shed by Christ himself. Learning humility is not a feat that can be achieved in a day, nor can one do it alone: it is a gift from God that can only be received, and one spends a lifetime learning how to use that gift in the context of a community. It may be that the course of humility resembles the themes of baptism, when a Christian partakes of Christi’s Pascha, with Christ himself nailing our capacity to sin to the cross. Baptism opens the door of humility to us, and living that Baptism each and every day makes it possible to accept our state in humility and to see others as they really are.

We have reflected on things that seem impossible: what is possible is for communities to commit themselves to cultivating a culture of humility and professing fidelity to dialogue. Our uncertain times generate fear of the unknown, and safe responses to the increasing intensity of annihilating one’s opponents are not bearing fruit. The absence of a Christian response to broken public discourse only breeds the growth of new layers of fear and anger that gain energy in a vicious cycle. An affirmative response to adopting an identity of humility, patterned after Christ, and committing to dialogue with others does not require one to capitulate their position. As Evdokimov said, humility is not self-humiliation: affirming the good that can be recognized when one considers the entirety of the other makes it possible to transform an enemy into a friend, as Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said in a beautiful homily on “loving your enemies.” This spiritual response to the broken public discourse of our time could turn the tide and make the peace that seems so elusive alive and well. In his Small Catechism, Martin Luther delivers the following teaching on the eighth commandment (Luther 2005, 321):

We are to fear and love God so that we do not tell lies about our neighbors, betray or slander them, or destroy their reputations. Instead we are to come to their defense, speak well of them, and interpret everything they do in the best possible light.

It is possible that Luther‘s teaching could become the norm, and not the exception, if Christians reintroduce a culture of humility and dialogue into public discourse. . May it be so. Thank you for your attention.

Works Cited

Basil of Caesarea. Saint Basil: Ascetical Works. Trans. Monica Wagner. Fathers of the Church series, no. 9. Washington: CUA Press, 1962.

Bellah, Robert N., Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, Steven M. Tipton. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Clements, Keith. “Ecumenical Witness for Peace.” In The Cambridge Companion to Dietrich Bonhoeffer, ed. John de Gruchy, 154-172. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Evdokimov, Paul. Ages of the Spiritual Life. Original trans. Sister Gertrude, S.P., rev. trans. Michael Plekon and Alexis Vinogradov. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998.

Halík, Tomáš. “Human Dignity in Interreligious Dialogue.” In Religion and Common Good, ed. Jarosław Pastuszak, 100-111. Olomouc: Institute for Intercultural, Interreligious and Ecumenical Research and Dialogue, 2015.

Harff, Barbara and Ted Robert Gurr. Ethnic Conflict in World Politics. Second Edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2004.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. Strangers in Their Own land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York: The New Press, 2016.

Judis, John. The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics. New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2016.

Luther, Martin. Martin Luther’s Basic Theological Writings. Second Edition. Ed. Timothy Lull and William R. Russell, foreword Jaroslav Pelikan. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005.

Pastuszak, Jarosław. “Anthropological Basis of a Dialogue – Christian Perspective.” In Religion and Common Good, ed. Jarosław Pastuszak, 164-180. Olomouc: Institute for Intercultural, Interreligious and Ecumenical Research and Dialogue, 2015.

Plekon, Michael. Living Icons: Persons of Faith in the Eastern Church. Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame Press, 2002.

Skobtsova, Mother Maria. Essential Writings. Trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Intro. Jim Forest. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2003.